Examples to Study Dynamics of Targeted Grazing for Unwanted Vegetation Management Using Goats

Introduction, Rationale and Significance

Small ruminants such as sheep and goats have an advantage over bovines in terms of size and adaptability to foraging and browsing. It is this distinctiveness which allows them to be used as an alternative to the use of herbicides or prescribed burning for tree farm planting preparation, rangeland improvement, or enhancement of recreational area landscape. In most states, significant portions of land are not used for agricultural purposes, and it is challenging to balance environmental, social and economic goals to achieve a sustainable forest management.

There are a number of anecdotal instances where goats have been used as a vegetation management tool, but limited resources have restricted efforts to organize and provide a continuous educational experience. Some of the forest or recreational areas –including wetlands, hiking trails, historic sites, and state parks — must be managed. The traditional clearing and preparation practices, such as prescribed burning or herbicide application, would compromise some of the foresters’ and park managers’ environmental goals. With appropriate planning and innovative strategies, goats can be used for clearing brush, vines, and saplings.

Historically, a definition of invasive species is very hard to isolate because it seems that every governmental agency and environmental advocacy group has a definition for it. In addition, the definitions seem to be dynamic, depending on the focus of the programs. For example, some related terms include alien, exotic, non-indigenous, non-native. For the purposes of this discussion we will use the terms “targeted grazing” and “unwanted vegetation management” interchangeably, to indicate use of goats for control of invasive vegetation. Bottom line: If the plant is not appreciated in an area and goats are capable of managing it or use it to produce some kind of animal product, then it is a win-win situation.

Unwanted plant species have infested vast areas of rangeland in the United States. Experts predict that thousands of acres will be invaded in the next years if forests or rangelands are not managed adequately. In general, invasive plants or noxious plants are often not as desired for the proposed habitat, crop or grazing; have no natural predators, or can decrease biodiversity by choking out native plants and limiting the number of different species growing in one area. There are reports that unwanted vegetation could change the soil characteristics by increasing erosion, decreasing nutrient content, and altering nutrient cycles (University of Arizona, 2010). The bottom line is that unwanted plants cost money and decrease land values, and worse, they can negatively alter fire patterns and frequency.

Plant invasions in forests and public areas have a huge economic impact. Conservative reports (Bergmann, 2010-Personal communication) put such efforts up to $120 billion/year, including agricultural losses and human health impact.

In order to manage unwanted vegetation using small ruminants in a targeted grazing program, operators need to know about sheep and goat behavior, plant physiology, plant structure, plant growth patterns, and plant species’ palatability/toxicity cycles, as well as have a clear end point in terms of the management goal (Escobar, et al., 1993). There are not many reported trials in the scientific literature about use of goats to manage unwanted vegetation. Researchers potentially could face many unpredicted situations and other factors; for example, the trials are affected by weather, and it is challenging to compare a “dry year” to a “wet year,” unwanted vegetation invasion is not uniform in every plot selected for the trial. In order to statistically account for every variation at the experimental site, the area would have to be very large or have small plots which would limit animal/plant interaction and could affect animal performance. The approach that seems to work the best is to ask ”Would sheep and/or goats eat this particular species?” Then, once that question is answered, “Yes,” steps should be taken to determine the animal units per area to obtain the desired results, either control or elimination of the unwanted vegetation.

Background and Previous Experiences

Following are three examples of successful use of goats to manage vegetation in rangelands and forest situations.

The first example of targeted grazing occurred with sand shinnery (Quercus havardii) which is a plant native in many thousands of hectares in western Oklahoma and Texas (Escobar, et al., 1995). Over time, sand shinnery can thicken above tolerable levels, limiting conventional agricultural uses and diminishing the more desirable native lovegrass (Eragrostis sp.). Chemicals, fire, mowing and mechanical methods have been used to manage shinnery with mixed results at a significant monetary cost. A demonstration sponsored by USDA/Forest Service, USDA/NRCS, Great Plains RC&D and Cooperative Extension Program/Langston University allowed the implementation of a trial, dividing 79 acres of the Black Kettle National Grasslands (Cheyenne, OK) into eight plots. Meat type, or Spanish, goats and Angora goats were introduced at different stocking rates and grazing strategies. The chart below shows the positive animal response expressed as body weight gain.

After three years of browsing with goats, frequency counts of plant species, expressed as percentage of species occurrence in sampling spots, revealed 55 percent oak and 59 percent lovegrass in the target pasture versus 100 percent shinnery and 20 percent lovegrass in ungrazed plots. Note that this is not a population count but times that the plant species, shinnery, lovegrass or both, were present in the sampling spots. Another benefit to the soil was that grazing goats allowed some of the vegetative nutrients to be recycled back to the soil. Soil tests revealed an increase in nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium and a slight decrease in pH. That information is condensed in the following table.

| SOIL NUTRIENTS CHANGE IN OAK SHINNERY PLOTS AFTER THREE YEARS OF GOAT BROWSING IN CHEYENNE, OKLAHOMA | ||

| Item | CONTROL PASTURE | GRAZED PASTURE |

| pH | 6.7 | 6.4 |

| N, lb/acre | 0.9 | 18.7 |

| P, lb/acre | 4.5 | 20.5 |

| K, lb/acre | 106.1 | 277.4 |

The second example of targeted grazing relates to the performance of goats grazing on sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), a noxious weed in Kansas (Escobar, et al., 1998). Sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata, fam. Fabaceae, 14.65 percent crude protein) has been regarded as a noxious weed in Kansas, because it is aggressive and persistent. Bovines do not have a particular appetite for sericea lespedeza and do not graze it. Early state surveys indicated that pasture invasion in Kansas reaches at least 30 percent of the area used for cattle grazing. The following table shows some of the data related to goat body weight gains during a three year trial.

Demonstrations were conducted at Lebo, Kansas, using goats to manage sericea lespedeza for three consecutive years. The first year, two groups of Spanish goats grazed the target plots. The second year, three types of goats grazed the target plots for 90 days. And, the third year, Boer crossed with Spanish female yearlings grazed sericea lespedeza for 157 days along with Spanish castrates. Annual plant counts in the trial plot indicated disappearance of mature sericea lespedeza plants after three years of goat grazing. Goat body weight gains showed that goats utilized sericea lespedeza. The results from the three-year demonstration, shown in the table, were encouraging to Kansas ranchers because it indicated that income could be generated from the growth of the meat goats while they were eating sericea lespedeza, a noxious weed.

| BODY WEIGHT CHANGES OF SEVERAL TYPES OF GOATS GRAZING SERICEA DURING THREE CONSECUTIVE YEARS IN LEBO, KANSAS | |||

| YEAR | Type of Goats (N) | Days Grazing | Individual Average Body Weight Gain, pounds |

| First Year | Spanish 1 (12) | 116 | 20.7 |

| First Year | Spanish 2 (37) | 37 | 8.0 |

| Second Year | Alpine (15) | 90 | 10.3 |

| Second Year | Angora (33) | 90 | 7.4 |

| Second Year | Spanish (19) | 90 | 9.9 |

| Third Year | Bore x Spanish (66) | 157 | 10.0 |

| Third Year | Spanish (80) | 179 | 22.0 |

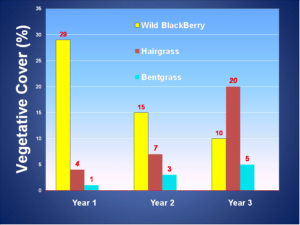

The third and last example of targeted grazing was at Roan Mountain, Pisgha National Forest in west North Carolina and Tennessee. The importance of this example is that animal performance was not a factor determining the success of the trial. The emphasis was on targeting wild blackberry (Rubus alleghaniensis) and Pennsylvania sedge (Carex pennsylvanica). The unwanted species were encroaching in very sensitive areas around the Appalachian Trail, where spraying herbicides was not an option due to the human presence in the highly traveled trail, which has about 4 million visitors annually. The other expected outcome was the re-establishment of desired rare grass species: hairgrass (Deschampsia flexuosa) and arctic bentgrass (Agrostis perennans). Wild blackberries grow as a tangled mass of thorny stems blocking access to humans, wildlife, and equipment. In addition, blackberries regrow following herbicide applications (University of California, 2002). The following charts show changes in the plant ecology of the trial site and a reappearance of the desired species.

Notice that after three years, the wild blackberry vegetative cover was reduced to 65 percent and the primary percentage dominance was greatly reduced. In contrast, the vegetative coverage of bentgrass and hairgrass increased by 500 percent of the coverage compared to coverage at the beginning of the targeted grazing trial. Also, there were incremental changes in the dominance percentage of areas where the grasses were present.

| CHANGE IN VEGETATION COMPOSITION AND STRUCTURE FOLLOWING THREE YEAR GOAT BROWSING TRIAL ON ROUND BALD, PISGHA NATIONAL FOREST IN NORTH CAROLINA AND TENNESSEE. | ||||||||

| % of Area Where the Species was the: | ||||||||

| VEGETATIVE COVER (%) | Primary Dominant | Secondary Dominant | ||||||

| Species | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Years 1 to 3 | Year 1 | Year 3 | Year 1 | Year 3 |

| SHRUBS | ||||||||

| Wild Blackberry | 29 | 15 | 10 | down 65% | 26 | 1 | 41 | 44 |

| GRASSES | ||||||||

| Hairgrass | 4 | 7 | 20 | up 500% | 8 | 23 | 2 | 16 |

| Bentgrass | 1 | 3 | 5 | up | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

In each of these three examples, the operators needed to be able to develop a plan to identify the unwanted species, the localization, season or vegetative state when plants were vulnerable to grazing/browsing, and how much the grazing and/or browsing would cost. Similar procedures could be used in other areas to utilize goats for unwanted vegetation control.

LITERATURE CITED

Arid Lands Information Center, Office of Arid Land Studies, University of Arizona, http://www.forestandrange.org/Rangeland%20Weeds%20module/sub8/p3.shtml. Accessed Jan. 5, 2010.

Escobar, E.N., T.S. McKinney, M. Moseley, R. Blackwell, S. Inglish and M. Rose. 1995. Impact of sand shinnery (Quercus havardii) after three years of goat browsing in Western Oklahoma. J. Ani. Sci. Vol. 73 (Supp. 1):134.

Escobar, E.N., H.A. Pearson, F. Pinkerton and J.A. McLemore. 1993. Use of goats for vegetation management. II Seminario Centroamericano y del Caribe Sobre Agroforesteria con Rumiantes Menores. Nov. 15-17, 1993. San Jose, Costa Rica.

Escobar, E.N., 1998. Performance of goats grazing on sericea lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), a noxious weed in Kansas. J. Ani. Sci. Vol. 76 (Supp. 1): 409, pg. 106.

Maryland Department of Natural Resources, Forest Service. http://www.dnr.state.md.us/forests/forester/mdfacts.asp. Accessed Jan. 19, 2010.

Maryland Department of Agriculture. 2009. Agriculture in Maryland Summary for 2008. Livestock Review, pg. 34.

University of California. 2002. Wild blackberries. Pest Notes, Publication 7434.

PERSONAL COMMUNICATIONS: Carole Bergmann, Forest Ecologist and Field Botanist, The Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission, Silver Spring, Maryland